Some Aspects of the Role and Status of the Women in the Music Life of Today’s Gambia1

(This article was originally published in 2002.)

The role and position of women in the music life of today’s Gambia is largely conditioned by the remnants of former social stratification. According to Gorer’s 1935 account, the jali / jali muso was the first person who touched a child at the moment of its introduction to the community and the last person to touch a dead body before it was laid in the ground (in Merriam 1964:139). On the other hand, some ethnic groups (for example, the Serer) believed that burying a griot in the ground would contaminate the soil or nearby springs, so they placed the body of a dead griot in the hollow trunk of the baobab tree (see Charry 1992:320). Such evident discrepancy between the role and status of musicians has continued to the present day and has been altered only to a small extent by the prestige of contemporary musicians, significantly intensified by their promotion in the mass media.

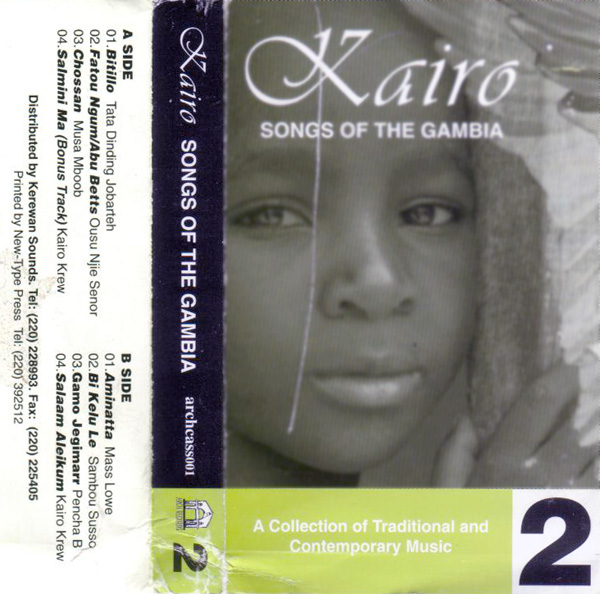

My interpretations of the role and status of the women in the music life of Gambia are partly based upon field research in Gambia during March and April of 2000, and partly on insight into the existing literature and recent local discographic releases. Two basic written sources (Ph.D. dissertations by Roderic Knight (1973) and Eric Charry (1992)) and two audio sources (Kairo I & II – Songs of The Gambia, representative local discographic releases) have pointed to the fact that the female segment of Gambian music is insufficiently recognised. Knight and Charry both emphasise the role of women in their dissertations, but they haven’t given them a lot of attention, since they were not a part of the specific area of interest in their research. On the other hand, the quantity of women musicians presented on the mentioned Gambian discographic releases reflects the marginalisation of women in contemporary musical industry of Gambia – only two out of fourteen musical examples are performed by women. Driven by these facts I have decided to try to find out through field research, whether they are really a genuine reflection of the role and status of women in Gambian music today.

In the essence of the issues I am dealing with here, lays a genteel semantic difference between the terms “musician” and “griot”, which is crucial for the study of the music life of today’s Gambia, regardless of the fact whether the centre of interest are male or female musicians. In the transformation of the definition of the term “musician”, starting from musician as exclusively a member of griot caste to the term “musician” which today refers to individuals of both griot and non-griot descent, the crucial role was played by the emergence of the mass media, the development and growth of local discographic industry, and the appearance of a new audience, mostly consisting of foreign tourists. These three elements have at the same time significantly changed the image of the music life of Gambia and increased the number of contexts in which the musicians perform today, but have also pointed to the evident changes in the way in which audience perceives musicians as well as to the need to redefine the term musician, primarily in the relation to the griot and non-griot descent.

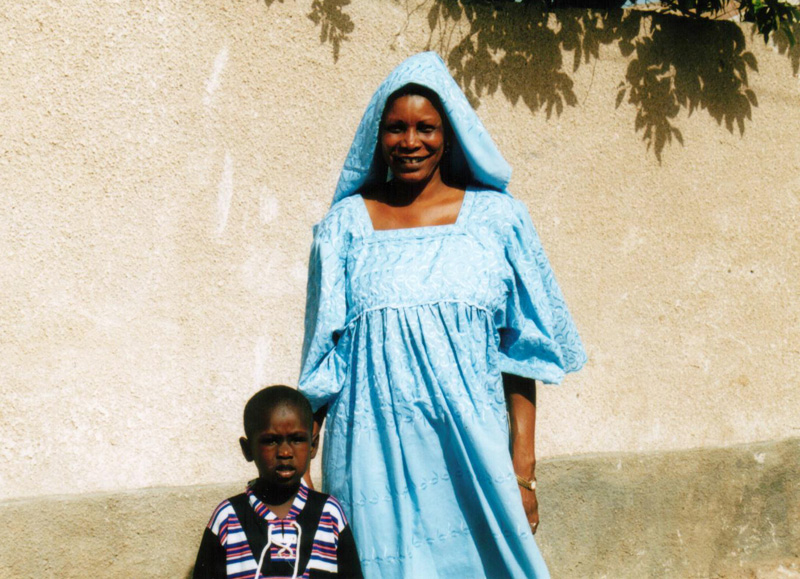

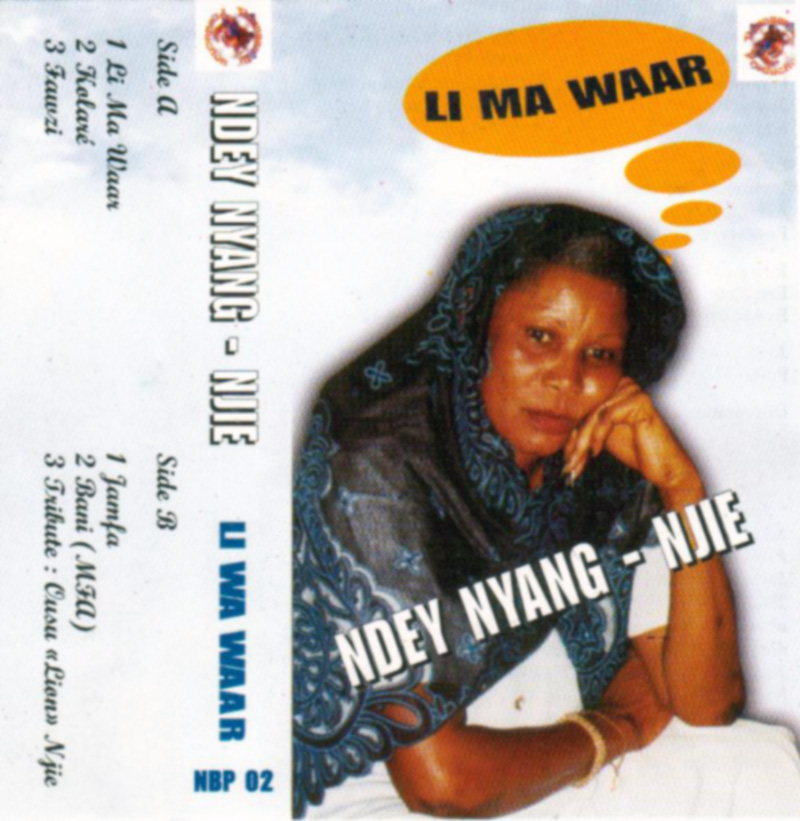

In my attempt to detect and emphasise the differences of the approaches to music and musical profession between the griot and non-griot musicians, and to analyse the role and status of women musicians in Gambian music, I have been greatly helped by two principal female informants – griot musician Kanku Kuyateh and non-griot musician Ndey Nyang Njie. I met Kanku Kuyateh through my balafon-teacher, and Ndey Nyang Njie through a journalist at the Gambian daily newspaper. My meetings with Kanku Kuyateh took place in her family home in everyday situations, that is, in the private sphere of her life, while those with Ndey Nyang Njie were held at her places of work (the Ndanaan-Bi Studio and the night-club in which she performs during the tourist season) or, in other words, in situations in which the public business sphere of her life was foregrounded. The core of this work is articulated around the juxtaposition of the expressed attitudes of these two musicians about various aspects of the musical profession.

Being a Jali or Simply a Musician? – Adjusting to the Changes of Tradition

The foundation around which the heterogeneous entity of Gambian music is articulated is made up of three historically and culturologically diverse segments. The first and oldest segment consist of the music traditions of ethnic groups, which established themselves as dominant in the Senegambian region during individual periods of pre-colonial history. That segment was initially made up of ethnically specific and, initially, separate music traditions, which were later drawn to each other through frequent migrations of the population, contacts between the groups, and the unavoidable processes of acculturation. These music traditions are usually identified and defined as African. The second segment emerged under Islamic influence and began with the first penetrations of the new religion during the 13th century. Today it is primarily represented in the sphere of sacral music, and, due to that fact is outside the focus of this article. The third segment is a reflection of the influences from Western European cultures, primarily British and French, and, in more recent times, North American. It was much less influential than the Islamic until the time when the music industry and the mass media started to expand, but from then onwards it greatly influenced the emergence of an equivalent of that industry in Gambia.

Gambia’s highly stratified society defined professional musicians in the past as members of the community whose profession was primarily conditioned by family heritage, that is, by belonging to a particular clan within a musician caste. In today’s Gambia, strictly separate castes no longer exist, but some of the patterns of previous social organisation have remained in everyday life. The remnants of the caste system still continue to shape the lives and activities of professional musicians to a considerable extent, and they also influence the way the society looks on individuals who work as musicians, but do not belong to the griot families. The historical beginning of the jalolu was linked with the person of Mansa Sunjata Keita, the founder of the Mali Empire. In Mandinka perception, and particularly in jalolu perception, the profession of jalolu gains its full significance in one event from the life of Sunjata, and for that reason the epic about Sunjata is the core of all of their repertoires, even today. One of the basic characteristics of every good jali/jali muso is the ability to improvise, both in the musical and narrative sense, so that the Sunjata epic has gone through many interpretations. Although the level of individualisation is very high in the numerous versions of the Sunjata epic, some of the common facts, repeated in the narrations of most jalolu, are accepted as historically relevant facts even in the contemporary writing of Mandinka history, and, consequently, the history of Gambia. The Mandinka noun jaliya corresponds in meaning to all aspects of the activities of the jalolu, which essentially are more than just music-making. Therefore, in various contexts it could be translated as “singing, playing an instrument, shouting praise names, asking for money, telling a story, composing a song” (Knight: 1975:58) or simply entertaining the audience. The primary task of the jali/jali muso is to praise the members of the patron family, and their ancestors who, as prominent members of the community, had important functions in the near or distant past.

One of the basic pre-conditions of traditional performances is the participation of the audience, which is familiar with the content of the epic. The virtue of each respected jali/jali muso lies in his/her ability to adapt to the audience for whom the performance is intended. In doing so, it is exceptionally important for him/her to know the genealogy of the family which is in the centre of his/her interest, that is, the family for which the epic is being performed on that particular occasion. The audience expects from jalolu, that during their performance, they create a family connection with some of the central characters of the epic and, in that way, glorify the family name.

Audience participation in the performance is most frequently seen in two types of response to the music event. When the jali/jali muso recounts the story of ancestors and mentions the family name, one of the family members usually responds with the word nam. The simplest translation of nam could be “yes”. By pronouncing it in the course of the music performance, the individual is letting the others know that he/she is both following the performance and is satisfied with it. Nam is also used as a sing of approval or praise for the performance, usually following some of the innovations in the textual or music segment. Another form of audience participation, which is of primary importance for the jali, is the material remuneration for a good performance. It can be given during performance, or at its end, and in more recent times it is being partially negotiated before the actual performance.

The term jali/jali muso has multiple meanings which makes it impossible to define it fully only with the term musician. Contemporary jalolu activities have been reduced largely to the music and entertainment segment on numerous new occasions in which they appear. Their impact, however, was much broader in the past, and still is on the majority of traditional occasions in which they are encountered today. Thus, Charry uses two terms to define jali/jali muso – musician and oral historian (Charry 1992:54). Despite the constant changes in tradition, the contemporary jali/jali muso has retained many of the tradition-determined functions, which exist today in new contexts. Kings and courts, which would require the permanent presence of the jalolu, of course, no longer exist in modern Gambian society. Since nowadays the jalolu are not connected exclusively with one patron family, they are in touch with a large number of individuals and/or potential commissioners of their services on a daily basis. Information about the attitudes of particular social circles obtained this way can be of multiple use to local politicians, this having contributed to the creation of a contemporary equivalent to the former ruler/musician relationship.

The musicians are assigned a low social position in an elaborate hierarchy, but their services – their ‘craft’ – is required at all levels. The combination of low status and high importance gives them access to a wide variety of people, places and events, but this artificial mobility in a predominantly closed system drapes musicians with a cloak of ambiguity to which non-griots respond with various degrees of social distance. Musicians regularly stand between separate levels in the social hierarchy, validating through witnessing the claims of super-ordinate people that they are generous and worthy of the respect of sub-ordinate people (Besmer 1989:12).

The position of the jalolu in the social pyramid is low and seems incompatible with the function, which they are entitled to, in a particular community. The status of the individual is determined by tradition and to a considerable extent defines what that society expects from him/her. On the other hand, as a respected member of community, the jali/jali muso enjoys trust so that the other members of the community often consult him/her, seeking advice on possible solutions for various problems or family disputes.

You can see one jali in the village taking care of all village problems. If any problem in any compound arises, he has the right to walk directly in that compound, speak to the people there and say to them: “Stop!” He will talk to them and make compromise and peace between the families. This is our work. And that is why respected people will always respect us and the work we are doing for the society.

(Alagi MBye, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

In such situations, the jali/jali muso, as a competent person, often invokes his/her knowledge of history, that is, he/she speaks of ancestors, their wise decisions and the right-minded things they did, and tries to influence people in conflict situations to do the same.

The economic aspect of the music profession depends greatly on the ability of the musician to elicit a fee during the performance, and also on the knowledge and respect of the tradition on the part of the individuals for whom he/she is performing. Their low position on the social ladder makes it possible for the jalolu to solicit material rewards from members of all the upper social classes. Apart from being the means by which the jalolu secure their existence, this practice also acts as a sort of a mechanism of social control. When the jali/jali muso seeks and accepts the reward for his/her skill, he/she is publicly admitting his/her inferior position and confirming the existing hierarchy. As a member of a lower caste he/she depends on the generosity of member of the classes with higher social rank. In such a situation, he/she takes on the role “of the mortar which both holds together and keeps apart the bricks” (Besmer 1989:18), which represent the strata of social hierarchy.

The reward which jalolu receive is not specified in either quantity or quality; it is left to the personal evaluation of the giver. However, in order to influence its value and to be in a position to express (dis)satisfaction with the gift, the jalolu make use of their verbal skills. As individuals whose opinions are respected and usually accepted, the jalolu are in a position to greatly influence the prestige of all individuals with their praise of criticism. Because of the fear of negative criticism and public disapproval the gifts given to the jalolu are often very valuable. Thanks to their verbal skills, it is possible for the jalolu to obtain considerable gain and even to attain a higher economic status than that enjoyed by members of higher castes, with the condition that they behaves in accordance with their inferior social position. Therefore, there is often a discrepancy between the economic and the social status of the jali/jali muso.

With the appearance of various popular music genres, primarily because of influences from the western music industry and globalisation, which had led to expansion of the market, a change has come about in the attitude towards the traditional profession of musicians and its foundation in the caste system. With the founding of the Gambian music industry and the influence of the considerably more developed and influential music industry of neighbouring Senegal, music has become more accessible and open to a broader circle of people. This has been reflected primarily in the structure of today’s music profession, of which griot musicians make up only a segment. The growing presence of non-griot musicians on the music scene has created new competition and intensified rivalry in the music profession. The economic status of the “new” (non-griot) musicians and the prestige brought by their appearance in the modern media often leads to the participation of popular musicians of non-griot origin in traditional ceremonies. This brings into question the necessity of traditional repertoire knowledge and everything that the jalolu do, while the emphasis is transferred to the entertainment aspect. There are still those jalolu who specialise in genealogy or the relating of history, but by far most jalolu are primarily musicians, with a vocal or instrumental emphasis, depending on their skills and inclination (Knight 1973:47).

The traditional element in the newly composed songs is usually retained by the selection of the instruments. The percussion section is almost always made up of sets of drums from diverse ethnic groups, while traditional melodic instruments (kora, balafon, xalam) also appear in some ensembles. In the performances the traditional instruments are often combined with the modern, such as keyboards, guitars and western drum set. Vocal interpretation follows the traditional ways of singing retaining characteristic ornamentation and specific nasal sound. In certain segments it becomes similar to declamation, which is one of the main traits of the vocal style in the improvised segments of traditional repertoire tunes.

Musicians of diverse family (griot and non-griot) and ethnic backgrounds are proportionately represented in the media, while their recordings and their public performances evoke equal interest among broad audiences, so that their musical identity is becoming evened out in the perception of the consumers.

The appearance of tourists, that is, foreigners, who form the new audience, has resulted in further changes in repertoire. The objective of the majority of hotel and restaurant owners is to ensure that they provide a sort of a musical background, which enhances the customary gastronomic offer. Here they are usually guided by the wishes of their guests, that is, they try to offer what they think the average foreigner expects from African music. The question of closeness to the music reality and traditions of Gambian ethnic groups is less important. And what does this mean for Gambian musicians? If they want to sign a contract with a restaurant or hotel owner for the performances during the tourist season, the are forced to offer the most heterogeneous and interesting programme possible, based on the stereotyped preconceptions of music perceived as African – usually drums and dance – purged of those parts of tradition which could be incomprehensible, too complex or even uninteresting to foreign guests.

On the one hand, the new audiences have removed some of the basic prerequisites for traditional music making. The first barrier between that audience and the performers is language. The new audiences do not know the local languages, cannot understand the texts of the songs, and by that very fact are not able to evaluate the skill of the musician’s verbal improvisation in the free segments of the traditional songs. This makes it unnecessary for the musician to know the genealogies and history, and makes redundant the basic elements of jaliya – singing songs of praise and glorifying the Mandinka families. To the jalolu, the new audience has no recognisable identity, and thus their relationship to it is undermined. The only level at which communication can be established is that of the music and the dance, which consequently becomes the primary focus of their interest in new context.

On the other hand, the demand for diverse repertoire has led to an integration of ethnically specific music traditions, which were detached in the past. Different instruments of one ethnic group, which were not used in the same ensemble in the past, now play together. Their further combination with instruments of other ethnic groups has led to the creation of a repertoire which, although ethnically diverse, is presented to the audience under the label “Gambian”. Since the major part of the foreign audience has almost no knowledge of the diverse Gambian music traditions, appearances of musicians who are not sufficiently trained in music are not rare. In the perception of the conservative jalolu, the appearance of these self-proclaimed musicians, and non-griot recording artists has caused confusion in the comprehension of their own identities. Today, jalolu are no longer the exclusive bearers of musical practice, which has been reflected in their economic status, social position and the privileges which derived from them. Such a combination of circumstances has let them to the question of how to reconcile tradition and modernity, that is, how to ensure their living and retain a place in the new, expanded music scene.

Being a woman musician in Gambia

A part of everyday life in both urban and rural communities is the sight of women using wooden mortars and pestles to pound rice, millet, maize, groundnuts and vegetables. Hand processing of foodstuffs in mortars is usually a joint task carried out by two or three women who live in the same compound and are responsible for preparing the daily meals. At first glance, performing this task has nothing whatsoever to do with music, but, nonetheless, it is a form of musical expression. Striking the grain in the wooden dish (kulungo, mand. – dish) with their wooden staffs (kundango, mand. – staff) results in specific rhythmic patterns. The sound intensifies as the task nears completion, since the level of the grain in the kulungo falls, and the kundango reaches almost to the bottom of the dish.

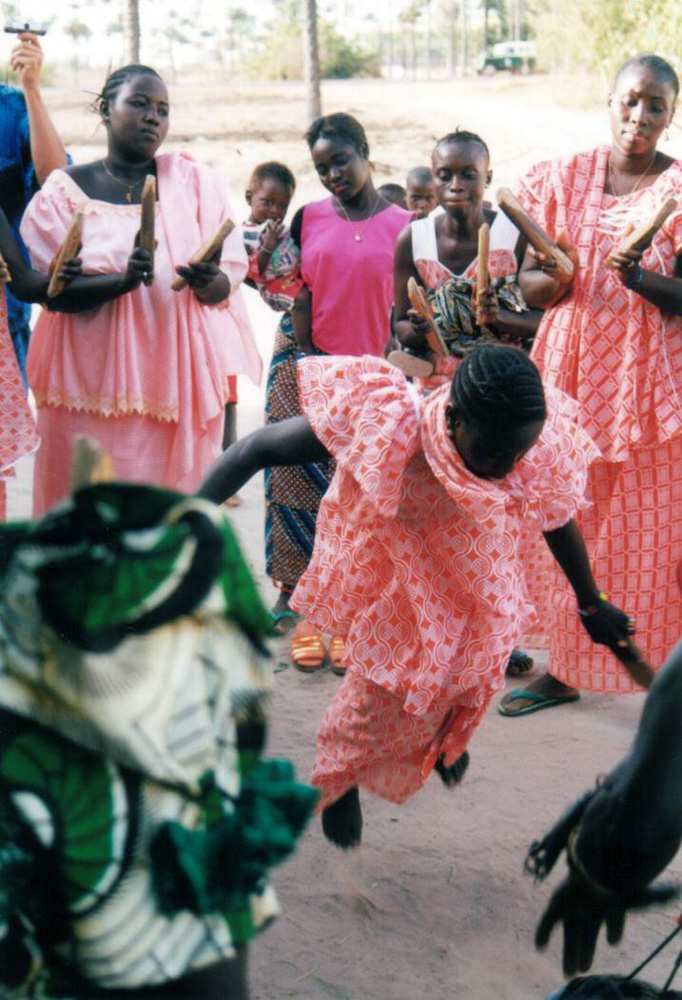

The mortar as a utilitarian musical instrument is also interesting because the rhythmic patterns performed on it make up the foundation of music which a child encounters early in its life, while comfortably placed on its mother’s back takes part in her everyday activities. The rhythmic patterns which women create by clapping their hands while standing in a circle and providing a rhythmical background for the dance are similar to those produced on the mortar (see Knight 1980:141). An excellent example of such rhythmic patterns is the bukarabo dance, which is performed by women of the Jola people. The participants in the dance event stand in a circle, set the rhythm with bamboo clappers, one by one enter the centre of the circle and perform characteristic dance steps.

Another non-professional female instrument is the water drum which serves to provide rhythmic dance accompaniment in the context of informal female gatherings, or is, in some situations, used in combination with other, professional or non-professional instruments.

Individual segments of the Sunjata epic are interesting historical sources about women in the music profession and the importance of the jali musolu in the history of the Mandinka people. When narrating the Sunjata epic, Alagi MBye emphasised three key moments in the life of Sunjata with which jali musolu are closely associated. At the same time, he criticised the behaviour of Sunjata’s jalolu:

Only when Sunjata had won control of the Manding empire did the men compose a song for him. Right up until then, they had been cowards. I probably should not say that, but only when Sunyata came to power and when they felt secure did they decide to speak up.

(Alagi MBye, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

Until then, according to MBye’s story, only women had been the ones who had sung for and extolled Sunjata. The first occasion upon which women sang for Sunjata was at the naming ceremony. Kulio is held on the seventh day following the birth of a child, and the jalolu are essential participants in that event. They play and sing for the guests gathered at the ceremony until the baby is carried out of the house and shown in public for the first time. Then the imam shaves the hair from the baby’s forehead, utters his name for the first time, and starts praying. After the prayer, the gathered jali musolu escort the mother and child into the house as they sing, accompanying themselves on the ne. The song which they performed at this time is considered to be the same as the one which the jali musolu had sung at Sunjata’s kulio.

Women are credited with the first song in the history of the Mandinka jalolu. This song is performed for each newborn baby in the Mandinka society, and it is performed only by women.

(Alagi MBye, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

Two other songs, which Alagi MBye considered exceptionally important in that context are connected with a specific person – jali muso Maniyang Kuyateh. When the exiled Sunjata was leaving the Mali Empire, she refused to keep silent as the other jalolu did and set out after him to see him off with a song, as was worthy of a king.

When Sunjata was departing in peacetime, the jalolu would accompany him, dressed in fine robes and announcing to everyone that the King was leaving. However, this time he was in conflict with his brother and the jalolu thought that he would kill them if they decided to accompany Sunjata with a song. Only Maniyang Kuhateh said: “This is bad… odd. I cannot bear it. I would rather die than see Sunjata leaving without a song.” She took up her ne and followed him singing.

(Alagi MBye, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

After the Susu king Sumanguru Kante had conquered the Mali Empire, Mandinka people decided that it was time for Sunjata to return from exile and to liberate them. They called on Maniyang Kuyateh to search him out and bring him home. The basic text of the song she then sang to him went as follows:

| Take up the bow and the arrow, |

| Take up the bow and the arrow, oh hero, |

| The war I sang of when you were leaving has begun, |

| Take up the bow and the arrow and return home. |

Alagi MBye’s narration shows how the jali musolu were respected members of the musician caste. In all three examples, the women are depicted as singers, and the sole indication of the instrumental segment is the mention of the ne. In Mandinka society, women singers were more respected than male singers, so consequently they were more often represented in music ensembles. The institution of the permanent patron has disappeared from the contemporary music profession. In order to ensure sufficient income, the modern jali is obliged to travel in the constant search for work, quite often even outside of Gambia. Travelling to distant places is much simpler and more profitable when the jali travels alone – without a female singer. However, despite the fact that today’s kora players are equally skilled in singing, ensembles in which the vocal parts are performed by a jali muso are much more respected.

The people who have the most to say about singing are the women, the jali musolu, because it is they who are recognised as the best singers. It is every instrumentalist’s wish to have an accomplished jali muso to sing with him, and a jali will often describe a very good male singer as “singing like a woman”, meaning that the beauty and style of his singing equal those of a woman (Knight 1973:77).

Jali Muso vs. Non-Jali Muso

When Knight spoke with jali musolu in Gambia during the 1970s about the characteristics of good singers, they all cited the same qualities in the same order: “(1) courage, (2) the ability to talk (meaning a command of words) and a knowledge of the proper words, and (3) a good voice” (Knight 1973:78). It is interesting how the hierarchy of the main characteristics differed in the comprehension of two of my informants. The first, Kanku Kuyateh, is a jali muso from a family, in which the music profession is an unbroken tradition. The second, Ndey Nyang Njie, is not from a musician family, but she is a well-known recording artist in Gambia.

Sometimes the female non-griot musicians bother me. Why? It seems to me that they hamper me in my profession. I was born in a jali family, a traditional musician family, and I am fully entitled to engage in music. I know the history of various families, and the non-griot female musicians do not. There are some jali musolu who do not have good voices, but they know how to talk and know everything necessary for the jaliya. This is what makes them different the non-jali female musicians (Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000).

I have jalolu friends. Many jalolu are my friends and they love me. I know some good jalolu, but I sing better than they do… Some jalolu sing better than I do, but I also sing better than some others do, although I was not born into a jaliya (Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000).

Family heritage and belonging to a griot family, in which music has been the traditional occupation through numerous generations of its male members, significantly influenced the professional path chosen by Kanku Kuyateh. As members of her mother’s family were of the blacksmith caste, most of her education and her first encounters with Mandinka music tradition were connected with her father’s music making.

As a child I often went with my father to attend the ceremonies at which he performed. After some time, he started to encourage me to accompany him in singing. I would sing those parts which I had learnt from him. That is how I started to sing and gradually I mastered many of the melodies that he sang. When I was fifteen I, too, started going to the ceremonies which were held in the neighbourhood. That is how I became independent.

(Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

Family support is very important for a jali muso at the outset of her engagement in the music profession. The family environment, in which music has a prominent role, both in the private and the professional sphere, is the starting-point and source of knowledge and skill. Therefore, Kanku Kuyateh herself gives considerable attention to the music education of her children.

Although my daughter is only four years old, I have started to teach her. For example, if we are at home alone and are doing the housework together, I try to transmit gradually my knowledge to her. In the beginning I choose simpler melodies. I sing to her, and she repeats parts of the songs. That is a good way to learn.

It is similar with my son [he was an 18-month-old toddler at the time of the research, note M.P.]. It often happens that there is not a single woman at home to look after him when I am performing. I never leave him with men, so I am forced to take him with me to some of the ceremonies. When I sing, as I did just now, he opens his eyes wide and turns his head towards me, listening as I sing. Sometimes when the men play balafon he approaches the instrument, takes the sticks and strikes the keys with them. That is also one of the ways to introduced him gradually into the jaliya.

(Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

Unlike Kanku Kuyateh, Ndey Nyang Njie did not have the support of her family. The position of the musician had been very low on the previous social stratification scale and this has remained almost unchanged. It is still present in the consciousness of members of the diverse ethnic groups of Gambia. Being a musician is regarded as a degradation of an individual whose family belonged to the upper social classes in the past. Parents in many non-musician families therefore condemn the serious music aspirations of their children.

Music never existed in my family. I am the only musician in my family and my parents never supported my inclination to music. My brothers even used to beat me so that I would forget about music, but I had made up my mind. In 1988, I performed for Gambian immigrants in Germany. It was only on my return that my family started to respect the work I was doing.

(Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000)

Ndey Nyang Njie calls her music Afro-Manding. Some traditional Mandinka songs are a part of her repertoire. A gift for music and expertise and skill in performing a large number of traditional songs are usually regarded as hereditary characteristics of members of the musician caste. It is therefore interesting to learn what Ndey Nyang Njie, as a female non-griot musician, thinks about her own music skills, affinities and the source of her knowledge:

I have always loved music, but I took it up quite late. As a child I lived with my father’s second wife and my childhood was difficult. I worked day and night and never had any time for myself. When I married, my first husband took me to Paris. I returned very disappointed and started singing in order to be able to forget my problems.

Where did I learn the traditional Mandinka songs? I don’t know. Perhaps it’s something spiritual. Perhaps it was a gift from God. I am a Wolof, but I sing in the Mandinka language. I spent a part of my childhood in Mali so my Mandinka is much better than my Wolof. I probably also heard some of the Mandinka songs there.

(Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000)

Unlike the jalolu, who often continue their training in music in the family of a respected jali, the jali musolu acquire the foundation of their future music-making only in their parental home. It is very important for the continuing of their music education and advanced training that they marry into the jali family. This type of marriage ensures them engagement in the music profession and life in an environment which will be able to recognise their value and appreciate their musical gift.

Many jali musolu state that no one taught them to sing or to engage in jaliya except their husband. This once again points up the recognition of singing as a skill that should come naturally, once the opportunity to put it to use is obtained in actual performance. The husband, while studying his instrument, learns singing by default. The wife, whether she has been trained or has simply absorbed the music around her, is placed by marriage in a position to put her voice to work, and this she does. Her husband is now her closest teacher and so the two work together for their mutual benefit (Knight 1973:88).

Endogamic marriages ensure the interest of the spouses, but at the same time represent a specific protection mechanism which enables preservation of the music traditions of particular ethnic groups. The jalolu guard their music tradition within the family. As they want to protect it they marry within their caste. A jali married to a jali muso will have a jali child. The jali and the jali muso will make wonderful music together. Just the way my wife and I do. I play the kora, and she sings so we can always develop in that way. If she, let’s say, was married to a man who was not a jali, he could simply say: “I don’t want you to go to those ceremonies. I don’t want you to sing.” So her talent would be lost. Such marriages destroy jaliya (Alagi MBye, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000).

Ndey Nyang Njie’s music making is also linked to her husband, but in a different context. She started her music career in the ensemble of her second husband, Ousou Lion Njie, now deceased. She sang the back vocals in that ensemble for years and her music identity is linked to a considerable extent precisely with her husband. Even today, two years after his death, she always introduces herself to the audience as Ndey Nyang Njie – wife of Ousou Lion Njie. A song dedicated to him, which features on her first album Li Ma Waar, has an important place in the repertoire which she presents in public performances. Once a year she organises a major concert in his honour, and brings together the best-known Gambian musicians. Although she constantly emphasises her husband’s influence on her music career, she believes that, as an independent woman today, who takes care of her family through her work, she is sending a certain message to all the Gambian women.

I am sure than I can influence people with my songs so that they start to think about women in a different way. Wherever I perform, I give women the message that they should not expect men to work for them. Women can earn their own money. I know that very well because I am one of such women. I work day and night to ensure financial support for my family. I depend on no one and each woman in the audience can be like me. When I lost my husband, everyone thought that it would be the end of my career, since, before, I had sung in his group and he had encouraged me to create my music. Although I have gone through many difficult situations in life, I am still singing. I think that sends a very powerful message.

(Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000)

The fact that, as a single mother, she is forced to take care of her family exclusively through her own work, has had considerable influence on the way she thinks of her profession.

Some male musicians here in Gambia think of their profession as pure fun. They drink and go out with many women and that is how they give the music profession a bad reputation. However, with me the situation is different. I think very seriously about my profession. Just like a president or a government minister, I get up very early and am already starting to practise at 8 o’clock in the morning, or to prepare for a performance or recording in the studio. My job is just like any other. I sing in order to be able to support my family. What I do is at the same time my profession and my love.

(Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000)

Both musicians I spoke to stressed the importance of co-operation with male musicians in everyday music situations. In the case of Ndey Nyang Njie, that co-operation ranges from promotion in the public media to the organisation of public performances. In answer to my question on the role of gender differences within the music industry and possible unequal treatment of male musicians and their female colleagues, she said:

I never think of myself as a woman. In the work I do I could also be a man. Everything I want to do, I have to do by myself. I compose my own songs. I arrange my music. I am the only female in my group, but I think of myself as a man. Moreover, being a musician is Gambia is as difficult for men as it is for women. In my opinion, there is no difference between men and women in this profession.

(Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000)

In the griot families in which the women are the only singers, the men actually depend on the women. A jali muso can go alone to a ceremony and sing there accompanying herself on a ne, while a jali who is skilled in playing only one of the instruments needs a female singer in order to perform at a ceremony. Within the framework of traditional ceremonies, there are, of course, moments in which individual tunes are performed in the instrumental version, but they serve as a type of intermezzo and are less attractive than the vocal and vocal-instrumental performances. So, the families, which organise a festivity do not invite ensembles which do not have a singer. If jali musolu go to performances alone, they are entitled to the entire fee and are not obliged to share it with their husbands or other members of their family. The decision of sharing the fee depends to an extent on what gifts she has been given.

Sometimes I am given money for my performance, sometimes clothes, and it happens that someone goes to the market, buys a bag of rice and gives it to me. If the ceremony is being arranged by a wealthier family, I can even be given a sheep or a goat.

(Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku 2000)

Today, a larger number of jalolu come to traditional ceremonies. Some are invited by the family while others simply turn up looking for work. In the distant and more recent past, all Mandinka families were connected to a certain jali family. When preparing the festivities, the family always bears in mind its jalolu and they are the first to be invited to participate. It is the duty of the jali/jali muso to accept such an invitation and to organise all segments of the music events which accompany the ceremony. He/she does, of course, also allow other jalolu present to perform in some part of the ceremony, but the audience gives the major part of the reward to him/her. Although individual jali/jali muso does not have the exclusive right to perform at the ceremonies of their patron, the tradition-based relationship between the patron and the jali/jali muso still ensures him the greatest material gain. It also enhances his/her status among the other jalolu present, improves his/her financial situation, and confirms inseparable connection with the patron.

My father is from Kantora [a region in Gambia’s east, note M.P.] and his family has always been linked with the local Sanyang family. I continued that tradition and my family and I are entrusted with all the events in the life of that family – naming ceremonies, weddings, funerals… Despite the number of other jalolu present at these ceremonies, they always invite at least one member of my family. If they invite me, their attention throughout the entire ceremony is concentrated on me, since the relationship we have is very deep. They do, of course, give something to the other jalolu, but most of what they give is always given to me.

(Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

The reason for the difference in the attitudes of the two female musicians lies in the evident changes in tradition. Music is no longer the field of activity exclusively of the jalolu. In the search for audiences, the lives of the musicians from the griot and non-griot families constantly intertwine. Rivalry is a bit more emphasised in the male sphere, because at the same time it takes place on two levels and in two diverse contexts. These two categories of musicians compete against each other in their efforts to be engaged for both traditional ceremonies and for performances in hotels and restaurants, while the female musicians, with rare exceptions, compete only for engagements in traditional contexts. In that sense, the female musicians from the non-griot families are much freer and the number of situations in which they can perform is much more extensive.

Female musicians from the non-griot families usually live in urban centres, since their success depends on the mass media and the recording industry. Therefore, they are, as a rule, in a much better economic situation than the majority of jali musolu. So, for example, they can afford transportation and escorts when they go out to performances at night and when they are returning home from them. It is quite rare to meet women in the street at night in Gambia, and if they find themselves outside their homes at that time they are almost always accompanied by a man. If women go out alone at night, as the female musicians from the non-griot families are forced to do, they risk losing their reputations and exposing themselves to sharp criticism, especially in conservative communities. The majority of jali musolu, who do their own housework and look after their families in addition to engaging in music, are not interested in late-night bookings in night clubs and restaurants. For them, traditional opportunities for music making are the sole source of income. Therefore, they emphasise their knowledge, singing skills, reputation and the rooting of their profession in tradition, in order to retain the exclusive right to music-making in traditional contexts and to keep the non-griot musicians at a distance for as long as they can.

Despite the constant changes in the music tradition and the shift which has occurred in the comprehension of music profession, a large number of observations from the jali musolu still find justification in the specific nature of the verbal and musical idiom of jaliya. Practising jaliya requires more than adequate vocal ability and knowledge of the basic verses and melodies of the traditional songs. The essence of jaliya lies in its free parts, and interpretation skill is attained only after years of learning and practice, along with constant work on perfecting the techniques.

The level of improvisation and individualisation differs from musician to musician, but this is much more important for singers than it is for instrumentalists. The most important factor for an instrumentalist is the complete mastery of the kumbengo, the basic instrumental ostinato used to accompany singing. The free part, the birimintingo, is performed only in intermezzos between the two performances of the vocal parts. The instrumentalist has to be familiar with the vocal expression, that is, the distinctive expression of the singer with whom he is performing, while it is important that the singer has a feeling for the flow of the instrumental part and starts singing confidently, precisely at the set moment.

A singer must always wait until the kumbengo is well established on the instrument, and then enter at the right moment. This is called kumbengo muta, the same term used to mean “hold the kumbengo only” on the instrument, but in this case “hold” means “grab” or “seize”. The accomplished singer can do this quickly and with assurance.

(Knight 1973:80)

In some songs, particularly those which belong to the older repertoire, the donkilo level – the unchangeable part of the vocal section – is already very demanding. This is because there is a large number of verbal formulae which have to be mastered. However, the sataro, the free improvisational part of the vocal segment of the performance, represents a particular challenge for the female singers. The sataro is the segment which leaves the singers with considerable freedom in choice of the subject of which they will speak in their performance. Depending on the situation, the sataro can relate to genealogy (mama jaliya), wise sayings and counsel (jali kumolu, mansalingo), but also to comment on current events, everyday situations, or even criticism directed at individuals, government structures or society as a whole. Both singers I spoke with emphasised that sometimes they could sing about some things, they could never have openly talked about in public. Apart from that, comment and criticism of any kind whatsoever, have a much more powerful effect when sung for a broad audience. Speaking of that aspect of their music making, both gave similar examples:

Sometimes I see or hear things which disappoint me. For example, if I visit a friend and his wife tells me that he is abusing her, I start thinking about how I could address the issue in public. At the next concert I sing about the problems of abused women and if that friend happens to come to the concert he could ask himself: “Is Ndey singing about me?”. Although I never mention directly the name of the person of whom I am singing about, he can easily recognise himself in my song.

For example, if I hear that my friend is being mistreated by her husband, I feel both ashamed and angry at the same time. The very next time a ceremony I am participating in is being held in their neighbourhood, I do something to mortify him in public. When he arrives at the ceremony, I greet him pleasantly, but as soon as I do that I speak to one the jalolu present with whom I am performing and call out to him: “Why do you beat your wife?” I pretend to be speaking to the jali, but I am actually addressing the husband of my friend. He knows that I am not criticising my jali, but speaking to him. He feels ashamed and perhaps that makes him stop beating his wife.

(Kanku Kuyateh, personal communication; Nema Kunku, 2000)

The jali muso is particularly powerful at the moment when she is in an environment which perceives her as a performer. At such times, the audience’s attention is directed to her behaviour and it registers everything that she says or sings. Respect for the jali/jali muso as a chronicler and competent commentator of social events, who has retained the right to openly criticise all social classes, is based in tradition. The freedom to criticise is unlimited, and his/her criticism is almost always accepted.

That aspect of jaliya has also been transfered into the popular music of West Africa. The international audience came to know the particularly influential music style of West African music through the works of female musicians from Wassoulou, the southern province of Mali. Their specific music idiom is known in their homeland and throughout the world as the Wassoulou sound. One of its most eminent representatives is Oumou Sangare and some aspects of her work have exerted powerful influence on female performers of popular music in other parts of West Africa – and also on Ndey Nyang Njie.

I really respect the Mali Wassoulou female musicians. In my opinion, they are much more important than the Senegalese female musicians. I almost always listen to their music at home. Those musicians, such as Oumou Sangare, sing about women issues and they sing the truth. They sing about real problems and they sing about them openly (Ndey Nyang Njie, personal communication; Serrekunda, 2000).

With time, Oumou Sangare has become an icon of Mali’s popular music. She has a huge audience, both in national and international terms. Through her advocacy of women’s rights in Mali society, she has become a model for a large number of modern Mali women.

Since childhood, I’ve always hated polygamy. My father had two wives. It was really a catastrophe. From a young age I started to sing, from nursery school, and I said the day that I take a microphone in front of a crowd of people, the first thing I’m going to do is I’m really going to deplore the people who marry four women, who engage in forced marriage. I had a lot of problems at first. At my concerts at the Palais de la Culture, the men used to wait in their cars. Their wives went into the concert and the men stayed outside. But a few men came inside and now more come. Lots of young women understood and really agreed with me. They had all that in their heads and were refusing forced marriages. When their parents tried they refused, but they could not express the pain they felt. So, now they had someone who could help them to cry out what they felt.

(Sangare, in Broughton et al. 1994:258)

Traditional tunes are represented on her records, but also her own compositions in which she speaks out about a broad range of current women’s issues. Her second album Worotan from 1996 is named after one of the songs which speaks of the subordination of women in marriage. There are also songs on the album which raise the question of the casting out of women who cannot have children, and about the injustice suffered by women forced to live in a polygamous marriage:

| “Married women, we are consumed with |

| anxiety if we do not have a child |

| Bless you Abdoulaye, Oumou’s son |

| A woman without a child is treated like a witch or a thief in our society |

| A childless woman is believed to bring bad luck |

| May God give a child to all women who desire one |

| A childless woman is thought to be a tell-tale in our society |

| Married women, the lack of a child haunts our spirit.” |

| (from the song, Denw) |

“Marriage is a test of endurance because The bride price of a mere 10 kola nuts turns the bride into a slave.” (from the song, Worotan)

| “Oh women if you have children within a polygamous marriage |

| Concentrate on the education of your children |

| Rather than the behaviour of your husband |

| A polygamous man is like a ronier tree |

| Those nearest to him do not benefit from his shadow |

| Women we must pray for God to take pity on us |

| For we have suffered enough |

| Women of the world, rise up, let us fight for our freedom |

| Women of Mali, women of Africa, let us fight for women’s literacy |

| Women, let us fight together for our freedom |

| So that we can put an end to this social injustice.” |

| (from the song, Tiebaw) |

These verses are from songs composed by Oumour Sangare. Similar attitudes also exist in the traditional repertoire songs of the Mandinka jali musolu. Although the texts of the songs are not as explicit as those in Oumou Sangare’s, identical messages can be read in them.

One of these songs is the song Banile. My informants described Banile as a woman’s song, alluding to the issues which make up its thematic basis. In the linguistic sense Banile is an interesting song, since the text is a specific mixture of the dialects of two Manding sub-groups – the Gambian Mandinka and the Mali Bambara. Individual versions of the basic text depend on the use of Mandinka and Bambara words.

| Refuse, refuse |

| Accepting or refusing can give you freedom in life |

| Some people have money, but they have no soul |

| Some people have gold, but they have no soul |

| Ah, refuse |

| Accepting or refusing can give you freedom. |

These verses primarily address women. The institution of the arranged marriage, conditioned largely by the economic status of the woman, still exists in Gambian society. This song is a form of criticism of that model in selection of a marriage partner. Some of the explanations given to me by the informants confirm that fact:

If a man meets a woman whom he wants to marry and tries to “buy” her with money or gold, she can reject him if she thinks that there is no love. It is her right to decide whether she wants to live freely or to tie herself to a man only because of his wealth.

(Alagi MBye, e-mail communication, 2000)

There is a general meaning of this song. There is a saying in West Africa which says: “I call gold. Gold is mute. I call cloth. Cloth is mute. It is mankind that matters.” In other words, although material things are important in life, it is love, freedom and the human being that matters in the end. Of course, one can choose material things, but putting these things before everything else, is like loosing one’s soul. To understand our humanity one must understand the nature of what makes us human. Thus, according to tradition, we become human through love and freedom.

(Sulayman Njie, e-mail communication, 2000).

A Shift between Genders, Contexts and Genres

Apart from the linguistic aspect, the interpretations of Banile also differ in the instrumentation and degree of free improvisation. In the course of my field research in Gambia I’ve encountered numerous versions of this song. Three interepretations – by Kanku Kuyateh, by Ndey Nyang Njie and by ensemble Sanementereng – appeared to be rather interesting in various aspects. Kanku Kuyateh’s singing was accompanied by two balafons, Ndey Nyang Njie is by a djembe, a traditional percussion instrument, a guitar and a keyboard musical instrument, while Sanementereng‘s interpretation was accompanied by a large drum ensemble. The data of duration of the performances is particularly indicative in the case of two female interpretations. Namely, Kanku Kuyateh’s interpretation lasts almost twice as long Ndey Nyang Njie’s does. The basic vocal segment, the donkilo, is the same in both performances, but the key differences emerge in the free, improvised part, the sataro. The sataro makes up a much larger segment in the performance by Kanku Kuyateh and provides a good example of the difference in interpretations by griot and non-griot female musicians. The griot singers possess a much large store of verbal formulae which they use in the sataro, and they are very skilful in the application of the learnt phrases in the various situations in which their performances take place. Non-griot female musicians base their performances on the basic text and the pertaining melody, and even the free parts of the text – subject to improvisation in traditional performances – are set ahead of time in their performances.

Kanku Kuyateh’s performance took place in an informal situation, similar, to a certain extent, to traditional occasions for performances that are not time-determined and in which spontaneous improvisations are integral parts of the performance. The decision on duration of the performance was entirely left to the performers. That was not the case with the studio recording made by Ndey Nyang Njie. The duration of each musical number was set and planned in order to create a homogenous entity together with the other numbers. Apart from that, individual levels – the instrumental and vocal segments – were recorded separately and the recording was subsequently polished during post-production.

The third accessible performance of the Banile song is interesting for a number of reasons. It differs from the previous two performances mostly because of its performance context. Sanementereng is a dance and music group which is made up of a variable number of djembe-players, one bass drummer (on djoundjoun drum) and a variable number of dancers. The members of the group come together for performances in restaurants during the holiday season, so their audiences are mainly made up of tourists. The group’s repertoire is adapted to audience tastes, and their basic objective is to present the drum-playing skills of African musicians. Inclusion of Banile in the group’s programme marks a transposition of a part of traditional repertoire, which takes place at several levels. The first level is contextual – a song which is otherwise performed in traditional contexts has been transferred to the context of performances for audiences of a completely different profile (tourists). The second level at which transposition occurs is on the gender definition level – what is primarily a “woman’s” song is performed by men. The third level is the one marking the transition from ethnically specific (Manding) repertoire to an ethnically neutral (heterogeneous) repertoire.

Adoption of the Banile song has, in Sanementereng‘s case, resulted in certain adaptations. While the instruments accompanying the singing are subordinate to the vocal in the traditional performance, the relation between the vocal and instrumental parts is quite different in the Sanementereng interpretation. In this performance, the sole task of the vocal segment is to accompany the events in the instrumental segment, and to ensure the recognizability of the song, so as to be able to differentiate it from others. Therefore, it is reduced to two stanzas of the donkilo which are repeated in the same form. The role of the singer has been taken over by the main dancer, but since the vocal expression is not the most important aspect in his performance and since he is not sufficiently trained in singing, slips in intonation are very frequent. The role of the choir in the typical call and response pattern has been taken over by the drummers.

All the changes in context within which the individual vocal and vocal-instrumental forms exist today are denoted by expansion of the traditional framework in which the music functions. They demand certain shifts in perception of the music by the conservative jalolu, who are inclined to regard such changes as signs of serious deterioration of tradition.

The project of releasing a large number of recordings intended to present the state of Gambian music at the end of the 20th century to the domestic and international audience, is also a part of the tendency to expand the contexts in which the music is performed and redefine the musicians’ profession, and their status in society. One of these releases – Kairo: Songs of the Gambia – presents renowned singers of various genres of popular and traditional music of Gambia. There are only two representatives from the female sphere of Gambian music in this release – the singers Sambou Susso and Siffai Jobarteh. Both of them are descendants of griot families, while the songs they perform on the recordings demonstrate two possible orientations among traditional female musicians on the contemporary Gambian music scene.

The song Bi Kelu Le, written by the singer Sambou Susso, is musically much more similar to the popular genres in Senegalese music than to Mandinka music tradition. The song’s love subject itself differs from the standard subjects in the traditional repertoire of Mandinka jalolu.

Many young jalolu responding to changing social patterns which have affected musical taste and the learning process as well, do not have the same respect for or knowledge of the past, and they opt for faster styles and more recent subjects because both have a more immediate appeal. The older or otherwise more traditionally oriented jali tends to scorn the newer styles, and especially the subject matter. Formerly jaliya was concerned only with the greatness of kings and warriors, and never with such undignified subjects as a girlfriend, a popular woman, or love. The traditionally oriented jali still looks down upon newer songs with these subjects as frivolous and a discredit to the profession (Knight 1973:73-74).

The only ethnically specific musical instruments which take part in the performance of the song Bi Kelu Le are the traditional percussion instruments of various ethnic groups in Gambia.

On the other hand, Allalekee performed by Siffai Jobarteh, is an example of the contemporary production of a traditional song which has, as such, found its place in a new context. Following Knight’s song categorisation, Allalakee belongs to relatively early repertoire (the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century), and Siffai Jobarteh’s instrumentation corresponds to the traditional mode of performance. The shift away from traditional instrumentation and a peculiarity of this performance is the featuring of a single-stringed west-African violin called the riti. Riti is a single-string fiddle of the Fula people of Senegal and Gambia and was not present in traditional Mandinka ensembles in the past. The use of this instrument in this particular performance is in accordance with the current trend of bringing together the instruments of various ethnic groups in a single ensemble which is usually denoted as – “Gambian”.

At the end…

If looked at superficially, the music tradition of the ethnic communities of Gambia, in which women are musically recognised only through vocal expression, while the men are also recognised through instrumental expression, could be interpreted as discriminatory to the female sphere. My interpretation suggests just the opposite, showing how in the majority of traditional and a certain number of modern music-making contexts, the men depend on the co-operation of women. The success of performances in diverse context depends precisely on this collaboration between women and men.

The position held by Kanku Kuyateh in the perception of the community is considerably different from her position within her family. In the family, in the professional sense, her position is on an equal footing with that of men, while in certain situations – particularly during traditional ceremonies – she is even more important than the male musicians in the family are. Equally so, in Ndey Nyang Njie’s public performances, men appear in the role of accompanying musicians and their music identity, their place in the music industry and on all the occasions in which they make music, are, to a considerable extent, defined by their working together with this female singer. Consequently, women are present and are more important in certain segments of the music life of Gambia than could be deduced by a survey of the literature and commercial music production in the country, through which efforts are being made to introduce the music of Gambia to an expanded audience.

References Cited

- Besmer, Fremont E. 1989. Hausa Griots: Social Stratification and Social Distance. [a paper presented at the annual Mid-Atlantic Chapter of the Society for Ethnomusicology].

- Broughton, Simon et al., eds. 1994. World Music. The Rough Guide. London: Rough Guides Ltd.

- Callaway, Barbara and Lucy Creevey. 1994. The Heritage of Islam: Women, Religion and Politics in West Africa. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Charry, Eric S. 1992. Musical Thought, History, and Practice among the Mande of West Africa. Princeton University (UMI 9302049 – PhD dissertation).

- Durán, Lucy. 1984. “Khalam”. In The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. II. Sadie, Stanley, ed. London: Macmillan Press Limited. 421.

- Durán, Lucy. 1984. “Ne”. In The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. II. Sadie, Stanley, ed. London: Macmillan Press Limited. 756.

- Gourlay, Kenneth A. and Lucy Durán. 1984. “Balo”. In The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. I. Sadie, Stanley, ed. I. London: Macmillan Press Limited. 117.

- King, Anthony and Lucy Durán. 1984. “Kora”. In The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. II. Sadie, Stanley, ed. London: Macmillan Press Limited. 461-463.

- Knight, Roderic Copley. 1973. Mandinka Jaliya: Professional Music of The Gambia – Volumes I and II. University of California (UMI 74-1573 – PhD dissertation).

- Knight Roderic Copley. 1980. “Gambia” In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Stanley Sadie, ed. London: Macmillan, 139-142.

- Merriam, Alan P. 1964. The Anthropology of Music. Evanston: North-western University Press.

- Suso, Bamba et al. 2000. Sunjata: Gambian Versions of the Mande Epic by Bamba Suso and Banna Kanute. London: Penguin Books.

- The author’s interpretation of the role and status of women musicians in the music life of today’s Gambia is based on an insight into the existing literature and recent releases of the local music industry and on a two-month field research in Gambia. In the past the identity of Gambian musicians was related to the strict social stratification, according to which music was the exclusive domain of the griots, members of the hereditary musicians caste. In the contemporary Gambian music life the identity of the musicians is greatly influenced not only by the relicts of the tradition but also by the growth of the music industry, the expansion of the mass media and arrival of tourists, which have in the course of time become the larger potential audience for local musicians. Such circumstances have led to the increasing appearance of non-griot male and female musicians, what has resulted in a keen competition between the griot and non-griot musicians, in performances for the local audience during traditional ceremonies, as well as when performing for tourists. The core of this work is articulated around the juxtaposition of the expressed attitudes of two principal female informants the griot musician Kanku Kuyateh and the non-griot musician Ndey Nyang Njie which show the evident differences in approach to, and contemplation about various aspects of the musical profession.